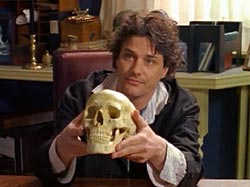

I, of course, have to respond to Jenna’s post and the photos

on Hamlet. First, it gives me the

chance for a brief cameo mention of Slings

and Arrows (“It’s not that heavy at all!”), which I’ve been waiting for. But, these photos - well, really, just this "image" of Hamlet and the skull is such an interesting choice on its own terms

because it really pushes the limits of iconism in regards to the performance

still. In fact, the Hamlet skull image might just bring the iconic

performance still to an utmost extreme.

I’m using Hodgdon to discuss this photo because, even though

she uses a version of this photo in her argument, I’d like to suggest that her

own analysis regarding this particular image outpaces her methodology in a way

that even she doesn’t account for. She specifically brings up the advertising

for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2001 production of Hamlet with Sam West. She focuses on this series of photos,

including the skull photo, during her most in-depth discussion of performance

stills as commodity. When she outlines her methodology at the start of her

article, she argues that the “theatrical still has a double history” because

“before and during the run of a performance, it takes life as a commodity,

teaser or provocation; only when the performance is no longer “up” does the

photograph reach the archive” (89). She then outlines her intent to explore

both the commodity and archival elements of performance stills in her essay.

Productions of Hamlet,

specifically the RSC’s 2001 production, tend to use performance stills from 5.1

in advertising. As Hodgdon points out, this is because of the “emblematic”

quality of this moment in Hamlet. She

uses the word emblematic, but then she undercuts the nuance of that term by

framing it with “recognizable but not clichéd” (108). The OED has several helpful definitions of “emblem”: “a drawing or

picture expressing a moral fable or allegory; a fable or allegory such as might

be expressed pictorially” (2a) and “a picture of an object (or the object

itself) serving as a symbolical representation of an abstract quality, an

action, state of things, class of persons, etc.” (3a). By using the word

“emblem” to describe this image, Hodgdon categorizes this photo at a level

beyond what her two-part methodology for performance still analysis (commodity

and archive) allows for. As the OED

suggests, an emblem was a visual symbol representing a narrative. Importantly,

in early modern England, emblems were used to communicate messages to a largely

illiterate society. By weaving together multiple well-recognized symbols into

one “emblem” that presented a very short and pointed story, emblem makers could

communicate with people who couldn’t read.

It seems to me that Hodgdon is right – that the image of

Hamlet with the skull does have an “emblematic” status. But this status seems

to result in more than just a useful, “recognizable” performance still for

advertising purposes. The result is that this image is not and cannot be

archived in the way Hodgdon suggests performance stills are after a performance

closes. So while these stills may be useful for commodification purposes in

advertising (although, as Jenna’s post suggests, even arguing that the Hamlet

and skull image can be a commodity in the way Hodgdon is suggesting seems

impossible – it’s almost reached the status of fetish, but a fetish to be

appropriated rather than one to be desired and/or purchased?), they can never

fulfill the archival function within Hodgdon’s argument. Other performance

stills can rightly serve as “the visible remains of what is no longer visible,”

as Hodgdon argues (89). But no one needs to revisit photos of Hamlet with the

skull to construct his or her own interpretation of this theatrical moment. This

moment in the play, and the countless times it’s been performed, are ingrained

in memory in a way that no other performance still has achieved because of the

overdetermined iconic status of this moment. I would suggest that performance stills of Hamlet with the

skull, no matter the performance, resist being archived. They represent

performance photos that will never be revisited, held, or analyzed for

reference because there’s no need for the material photo in a case where the

abstract idea has taken on the archival qualities of the material.

No comments:

Post a Comment